Des Moines, Iowa, USA

Intervista a Daniele Pantano per Jona Editore, maggio 2020.

La poesia di Daniele Pantano arrivò per la prima volta alla mia attenzione in lingua originale, nella sua pubblicazione americana di alcuni anni fa. Mi colpì da subito, tanto da segnalarla ad Emerging Writers Network tra i dieci migliori titoli dell’anno. Ora sono a dir poco felice di vedere il suo lavoro tradotto e, naturalmente, ho colto al volo l’occasione di intervistarlo che mi è stata offerta da Jona Editore. Considerando che Daniele vive vicino a Leeds, in Inghilterra, e io in Iowa, negli Stati Uniti centrali, abbiamo gestito le nostre domande e risposte via e-mail.

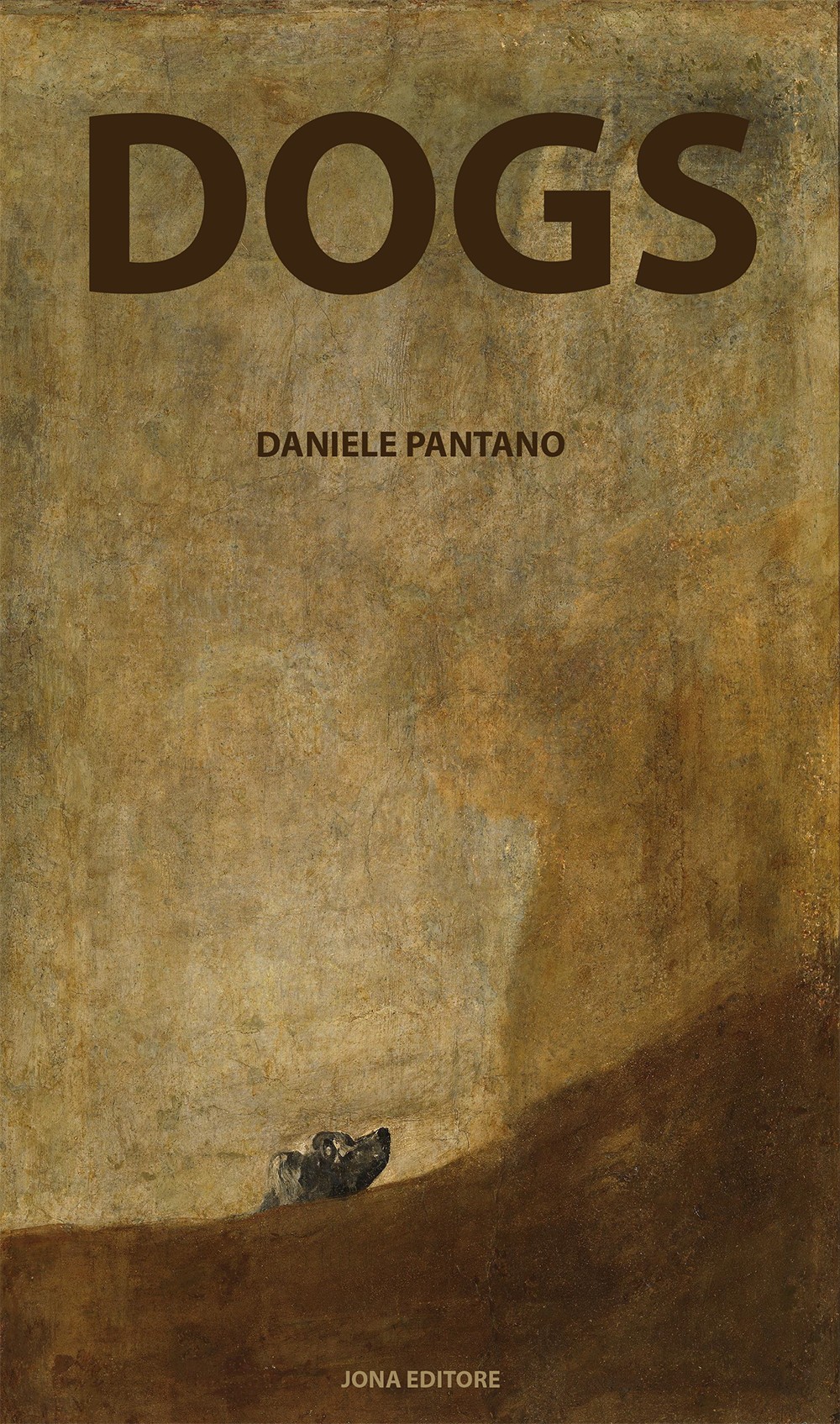

Questo libro serba tante piccole sorprese. Il titolo “DOGS”, per esempio, ha un che di grezzo, di approssimativo, fa pensare ai cani di strada, mentre – per contrasto – molte poesie suggeriscono una profonda e raffinata cultura, con le sue immagini simboliche, pietre miliari della storia europea. Un primo esempio significativo è “Tra le Stazioni della Metro”, che fa chiaramente riferimento alla nota poesia di Ezra Pound “Nella stazione della metro”. Come hai deciso di servirti di un riferimento, di un contributo simile, per questa poesia in particolare e per la raccolta in generale?

Vorrei innanzitutto ringraziarti per la generosa lettura delle mie poesie e per le tue preziose parole, John, che apprezzo molto. Come sai, sono sempre stato un grande ammiratore del tuo lavoro ed è molto emozionante poter intavolare con te questa conversazione. Il titolo si basa sulla versione originale dei miei Selected Poems, Dogs in Untended Fields, che è già stata pubblicata in inglese e in tedesco, e che sarà presto disponibile anche in francese, albanese, russo, sloveno, curdo, persiano, spagnolo e in qualche altra lingua. Per qualche strana ragione, la traduzione letterale del titolo non funzionava molto bene in italiano, quindi abbiamo deciso di scegliere una versione abbreviata per l’edizione italiana, appunto. Quindi, devo dire che hai ragione: non abbiamo di certo a che fare con simpatici cagnolini imbellettati da preziosi collari, qui; si tratta di cani selvaggi, come quelli in cui ti potresti imbattere sulle colline siciliane. Se mi identifico con quei cani selvatici? Sicuramente. E per quanto riguarda le poesie, la maggior parte delle quali sono state scritte tra il 1997 e il 2012, si tratta essenzialmente dell’inventario del mio processo di sviluppo come poeta; dei miei incontri con le “culture” che si trovano su un altro livello rispetto a quello della classe operaia in cui sono nato; dei quesiti che ho posto a me stesso sulle diverse storie europee; i miei tentativi di dare un senso al mondo in cui vivo e ai codici attraverso cui si esprimono il dolore, il trauma, l’esilio; dei miei sforzi per vivere una vita autentica, quella che mi hanno sempre detto che un cane bastardo come me non merita.

Soffermandoci sulla questione dei rimandi culturali, vorrei chiederti qualcosa sulla tua storia. I tuoi genitori provengono da paesi molto diversi, Sicilia e Germania, hai insegnato negli Stati Uniti e in Inghilterra e trascorri molto tempo in Svizzera. Senza dubbio questo miscuglio culturale ha dato una bella mano a plasmare la forma dell’intera raccolta, ma mi piacerebbe sapere cosa hai da dirci più in particolare al riguardo.

Sì, questa è una domanda che viene spesso fuori durante le interviste. Ed è una lunga storia, come puoi immaginare, ma eccoti quella breve: da bambino immigrato, nato in Svizzera (da padre siciliano e madre tedesca), sono sempre stato visto come una sorta di strambo animale dai sogni irrealistici, soprattutto quando mi è venuta l’idea di diventare un poeta. La società svizzera e il suo sistema educativo hanno fatto del loro meglio per essiccare la mia corteccia e tenere la gabbia ben chiusa. Non mi fu permesso di sostenere gli esami di ammissione alle superiori perché ero considerato straniero. Il mio insegnante della scuola secondaria mi disse: “agli italiani idioti come te non frega niente di andare al liceo”. Ho fatto domanda per diversi apprendistati ma, di nuovo, sono stato respinto su tutti i fronti. Mi sono reso rapidamente conto che dovevo lottare duramente per poter avere una possibilità di istruzione superiore creandomi delle opportunità fuori dalla Svizzera. Alla fine, sono riuscito a svignarmela, ingannando un noto talent scout del tennis di Zurigo e convincendolo a darmi una borsa di studio per frequentare una delle più prestigiose accademie di tennis e scuole preparatorie degli Stati Uniti, anche se non avevo mai frequentato una lezione di tennis in vita mia. Dunque, sono riuscito a prendermi il diploma di scuola superiore, che mi ha permesso di frequentare un’università americana e, cosa più importante, che mi ha offerto l’opportunità di diventare uno scrittore, un poeta, una persona che gioca con le parole. Il mio esilio autoimposto e il suicidio linguistico, cioè la mia decisione di scrivere esclusivamente in inglese, mi era necessario per vivere una vita da scrittore, per lavorare sulla mia identità artistica e seguire letterati del calibro di Simic, Brodsky o Nabokov in lingua inglese, in quello spazio non translinguistico in cui vivo da quando avevo diciassette anni. Scrivere poesie mi ha permesso di vivere la vita dello scrittore, di girare il mondo, di insegnare a migliaia di meravigliosi studenti negli Stati Uniti e in Inghilterra, e molto altro ancora. La mia attuale carriera vuole anche essere una sorta di “vaffanculo” finale per i miei ex insegnanti in Svizzera, ma, cosa ancora più importante, dimostra a molti dei miei studenti – tra le altre cose – che, nonostante quel che si dica, tutto è possibile, non importa chi sei o da dove vieni.

Affascinante, e incoraggiante anche per il modo in cui hai superato il pregiudizio. Se dovessi applicare questa storia che mi hai raccontato a una poesia in particolare, potrebbe essere “Studio sulle polveri sottili e Soluzione Salina Ipertonica”. I versi di apertura combinano l’idea di un “nessun luogo” a cui si arriva con l’immagine gioiosa di “ci sarà sempre un carnevale”. Quella poesia si riferisce al tuo mash-up personale, o magari sbaglio? Potresti fornirmi tu qualche altro esempio?

Posso dire di aver scritto Studio sulle polveri sottili e Soluzione Salina Ipertonica durante il mio tragitto giornaliero in treno da Liverpool a Ormskirk (nel 2009, credo), mentre insegnavo alla Edge Hill University. Affronta l’dea di esilio e di trauma, ma sonda anche le possibilità di speranza e il bisogno di arrivare alla fine del percorso con qualsiasi mezzo possibile, non so se mi spiego. Penso che tutte le mie poesie, in un modo o nell’altro, affrontino il mio “mash-up personale”. Vedo il mio lavoro come una lunga “confessione”, ma non significa necessariamente che si tratti di una poetica “confessionale”. Le mie poesie riguardano in realtà il linguaggio, la riscrittura dei nostri miti (alla fine, tutti noi creiamo i nostri miti, giusto?), e come questo codice espressivo trovi sempre un modo per farci sentire irrequieti.

Ah, confessione e mito: questo mi porta a una delle poesie più intriganti “La stagione di Trakl”. Georg Trakl era un poeta austriaco dell’inizio del secolo precedente, e ammetto di aver avuto bisogno di fare un paio di ricerche per aiutare la mia memoria ormai pericolante. Ogni lettore può notare da sé come la tua poesia sia in grado di coinvolgere il mondo naturale, come, che ne so, un acero o una brezza, con il solo potere della voce e della confessione. Allo stesso modo, dà vita a fantasmi, soldati morti e “anziani pellegrini”. Tutto sommato, mi ricorda un poeta molto più famoso, Ovidio, e le sue “Metamorfosi”. Cosa puoi dirci di questa straordinaria poesia e di come ha preso vita?

Il fantasma di Trakl perseguita tutta la mia produzione. Leggo la sua opera da quando ero un adolescente, attraverso lo studio della sua ineguagliabile abilità nell’usare una gamma di colori e “oggetti” molto limitata per creare visioni da incubo che si nascondono in una bella immagine: ha avuto una grande influenza su di me. Ho anche tradotto e pubblicato le sue poesie, molti anni fa ormai –– vedi il mio approccio concettuale più recente in ORAKL (Black Lawrence Press, 2017). E, in qualche modo, ha continuato a saltar fuori durante la mia carriera accademica, soprattutto negli anni della scuola di specializzazione, quando lavoravo con Franz Wright, Nicholas Samaras, James Reidel e Daniel Simko, che erano anche studenti di Trakl e che mi hanno ricordato e incoraggiato a fidarmi della voce della natura e a registrare le sue confessioni, quando lavoravo al manoscritto della mia prima raccolta. Comunque, La stagione di Trakl è semplicemente un omaggio alla sua persona, un riconoscimento delle sue influenze sul mio lavoro di poeta e traduttore letterario. È bello vedere, tuttavia, che la poesia è in grado di dar vita ad altri fantasmi.

Scendendo più nei dettagli di DOGS e in particolare nella poesia “Artista in Fuga”, c’è un verso che risuona forte e chiaro, come una sorta di ossessione, direi. Il pezzo è una specie di elegia per tua madre e, a un certo punto, parla di “Linguaggio, annidato nel silenzio”. Questo ci riporta ancora una volta al concetto di confessione, al comunicare per esporre la propria interiorità e, ancora, al concetto di un mondo senza voce che ha però una sua anima. Cosa puoi raccontarci di questo verso, di questa poesia e del loro significato nel complesso?

Questa, per me, non è una domanda facile a cui rispondere. La poesia riguarda il funerale di mia madre. Il modo in cui si è uccisa. È una confessione, una registrazione di ciò che è accaduto durante il servizio in chiesa. La sua bara scomparve e ci vollero ore per trovarla. Ero ancora abbastanza giovane. Il resto è nella poesia, che si domanda anche: quale lingua può eventualmente affrontare questo tipo di perdita? Come parliamo per esporre l’anima quando l’anima è stata messa a tacere? Come possiamo catturare in dei versi un mondo che improvvisamente ha perso la sua voce, la sua capacità di parlarci? Non lo so. Ma forse è esattamente quello che sto cercando di realizzare nelle mie poesie: trovare i silenzi che parlano, i silenzi che – come una volta disse Roberto Bolaño da qualche parte – sono “stati creati apposta per noi”.

Bolaño ovviamente è un artista potente, ma il potere delle tue poesie assume una forma diversa, più personale, che considera anche i dettagli più insignificanti dell’esperienza. Lo vedo anche da quest’ultima risposta e dal modo in cui questi versi riprendono i tragici eventi che li hanno ispirati. Comunque, se si tratta di una domanda difficile, sorvolerei: cosa puoi dirci, invece, della relazione tra immaginazione e realtà? Da che parte si trova la tua Musa? Se servisse un riferimento a una specifica poesia, per rispondere alla mia domanda, vorrei suggerire “Vita di Montagna” che parla proprio della scrittura stessa.

Realtà e immaginazione, per me, sono la stessa cosa, o almeno vanno di pari passo. Nella sua forma più elementare, la scrittura è l’atto di tradurre il “reale”, ovvero gli eventi, in un linguaggio che tenti di decifrare ciò che crediamo sia vero (il nostro tentativo di dare un senso al mondo), indipendentemente dal fatto che stiamo parlando di emozioni, oggetti, alberi, insomma, di qualsiasi cosa. Ed è proprio l’immaginazione che consente questo processo. Nella migliore delle ipotesi, il risultato ci offre una sorta di interpretazione della vera natura del reale, cioè il noumeno, la cosa in sé. Sai cosa significa sperimentare la vera perdita? O il vero amore? O la vera depravazione? Non lo sappiamo. Non sappiamo davvero nulla di nulla. Eppure, alla fin fine, la poesia è l’unico veicolo che ci offre una possibilità per avvicinarci di almeno un passo alla cosa in sé, e l’immaginazione (la Musa?) è l’ingrediente segreto di tutto questo; ci consente almeno di immaginare come potrebbe essere il vero, la “realtà” non filtrata di qualsiasi esperienza. Come tale, la poesia offre possibili verità in assenza di verità assolute. Come dico sempre, nel migliore dei mondi possibili, la poesia è estremamente importante e, al tempo stesso, assolutamente superflua; la poesia cambia tutto e non cambia niente. Dove volevo arrivare, con questo discorso a proposito dei versi su mia madre? Tutto nella poesia è vero, comprese le citazioni. È successo esattamente come lo descrivo. Però, non saprò mai cosa sia successo realmente. Ne abbiamo già avuto abbastanza della mia poetica kantiana? Secondo me sì. Continuiamo a vivere nell’incertezza, dunque, e immaginiamo cosa possa ancora essere possibile – almeno all’interno e attraverso la scrittura – che è quello che ho fatto in Vita di Montagna. L’ho scritta quasi due decenni fa ma, solo di recente e inaspettatamente, ha preso vita, con l’essenziale differenza che, mentre la poesia perfetta non è ancora arrivata e mai arriverà, non sono stato io ad essere partito a bordo di quel traghetto.

Dunque, hai detto che “la poesia ha preso vita”, che è diventata la parte migliore di sé, il suo “noumeno”. Altri artisti, non soltanto i poeti, hanno descritto questa stessa esperienza. Ci sono dipinti di Picasso che sono, in realtà, ri-dipinti; sembravano essere dei lavori completi, ma li lasciò in sospeso per un po’ e poi, in qualche modo, fu in grado di scorgere attraverso la tela un’altra immagine, più autentica. Non pensi che, all’interno delle tue poesie, si registri tale processo in divenire, per esempio in “Simic e il suo esercito di Ragni”?

Be’, no, Vita di Montagna, una poesia che ha ormai diciotto anni, prende letteralmente vita, la peggior vita possibile; io e mia moglie ci siamo separati già da qualche anno, e solo ora riesco a toccare con mano i particolari più dettagliati della questione. Come ho già detto, la poesia, rispetto alla prosa o alla pittura o alla fotografia o ai film – per fare alcuni esempi – si avvicina alla verità senza mai catturare veramente l’esperienza vissuta o la vera natura dell’esistenza: la poesia resterà per sempre incompiuta. Siamo per sempre incompleti. Picasso sarebbe d’accordo, penso. Era in eterno conflitto con il compiuto. Distrusse tutto ciò che gli sembrava completo, da qui la sua ricerca di ciò che andava al di là dei dati fisici del suo lavoro. Ora, Simic e il suo esercito di Ragni è un’ars poetica incorniciata da un partito immaginario che Simic decide, appunto, di radunare nel seminterrato di casa sua, dopo aver vinto il Pulitzer nel 1990. Proprio così. E quel “regno di luce” della poesia, è il noumeno dell’esistenza che ci sfugge, il cadavere del poeta, ovviamente. È quella luce che si trova dentro e oltre tutti noi.

Ragni indaffarati, altre creature, radici, frutta e verdura: il mondo naturale continua a farsi largo e a germogliare ovunque. La nostra conversazione mi fa pensare che tutto faccia parte della ricerca di questo “noumeno”; in fondo, esiste forse niente che sia più “cosa in sé” di un animale o di un fiore? A ogni modo, la forza della natura – cercando il sole – conferisce alla tua poetica un certo ottimismo. Lo si nota soprattutto in “La Teoria del Caso”, con i suoi “raccolti in mezzo allo splendido degrado”. Cosa ne pensi di questa lettura?

Sì, mi trovi d’accordo! Qui c’è un certo ottimismo, anche se la poesia parla di traumi e dell’impossibilità di tornare al vecchio sé, del permanere delle nostre cicatrici. Qui, la luce (artificiale) dell’ottimismo che tutti cerchiamo è rimasta purtroppo nascosta nella cantina delle nostre radici, assieme al resto del raccolto dell’anno, mentre tutti vaghiamo nei nostri giardini incolti, scavando nella terra, alla ricerca di un ultimo segno di speranza.

Penso che adesso sia giunto il momento di alleggerire la conversazione. Le tue poesie mostrano anche un istinto di assurdità, oserei persino dire un senso dell’umorismo. Al funerale di tua madre, per esempio, sentiamo il borbottio di un pazzo. Una giustapposizione del genere fa scaturire una risata improvvisa e sembra essere un particolare centrale in “Domino-Apertura”. Cosa puoi dirci, in generale, e in particolare di questi bizzarri compagni di letto che hai deciso di accoppiare in questi versi?

Assurdità? Sì, può essere. Ma, addirittura, “senso dell’umorismo”? Sei il primo scrittore o lettore che abbia mai scorto del senso dell’umorismo nel mio lavoro. La prenderò per buona, mi offre uno spunto su cui riflettere! La mia prima risposta, comunque, sarebbe sempre la stessa: “Non scrivo poesie divertenti” –– mi ricorda un verso di Jack Gilbert, che dice: “I pescatori greci non / giocano sulla spiaggia e io non / scrivo poesie divertenti.” Ora, in realtà, il concetto di follia e la figura del matto sono due cose che mi interessano molto, sì, ma lasciamole per un altro giorno o per un’altra domanda. Ad ogni modo, “Domino - Apertura” è semplicemente un’indagine o una riflessione sulle relazioni umane all’interno di uno spazio, o di un non-spazio, creato dal caso e dal caos: quello di cui sono composte tutte le nostre vite, essenzialmente. Sono consapevole del fatto che io stia continuando a evitare di rispondere alle tue domande su poesie specifiche, e ti faccio le mie scuse. Non sono in grado di spiegare le mie poesie. Di fatto, semmai, le mie poesie sono le spiegazioni, il modo più diretto e conciso che ho per parlare di uno specifico argomento. E, una volta che l’ho fatto, non c’è più lingua. Questa poesia, tuttavia, è importante per me in quanto è un esempio di una poetica più sperimentale e linguisticamente innovativa. Credo che, qui, il linguaggio dia il meglio di sé e si carichi di possibilità quando viene trattato come un semplice mastice, quando le giustapposizioni – ad esempio – vengono fuori in maniera naturale, quando i versi sulla pagina “eseguono” piuttosto che “produrre” il linguaggio: la poesia del dire contro la poesia del detto, come dice Robert Sheppard. Insomma, direi che in DOGS c’è un buon equilibrio tra il dire e il detto, direi che c’è qualcosa di buono per tutti, o almeno lo spero.

English Version

John Domini

Des Moines, Iowa, USA

Daniele Pantano interview, for Jona Editore, May 2020.

Daniele Pantano’s poetry first came to my attention in English, in its American publication, some years ago. I was so impressed, I selected his book among one of that year’s ten best, for the Emerging Writers Network. Now I’m overjoyed to see his work translated, and naturally I jumped on the chance to interview him. Since he lives near Leeds, England I in Iowa, in the central US, we handled our questions and answers via email.

Your book has some fine surprises. The title, for instance, has a rough quality, it makes one think of street dogs—but many of the poems suggest high culture or touchstones of European history. A telling early example is “Between Stations of the Metro,” which plainly references Ezra Pound’s famed poem “In the Station of the Metro.” How do you see such a reference working, contributing, both for this particular piece and for the book as a whole?

Let me first thank you for your generous reading of my poems and your kind words, John, which I appreciate very much. As you know, I’ve always been a great admirer of your work, and it’s very exciting to be speaking with you via this Q&A.

The title is based on the original version of my Selected Poems, Dogs in Untended Fields, which has already been published in English and German, and which is forthcoming in French, Albanian, Russian, Slovenian, Kurdish, Farsi, Spanish, and a few other languages. For some reason, the literal translation doesn’t work very well in Italian, so we’ve decided to go with an abbreviated version for the Italian edition. So, you’re right, we are not dealing with cute lapdogs with pretty collars here; these dogs are the wild ones you meet in the hills of Sicily. Do I identify with those wild dogs? Most definitely. And the poems, most of which were written between 1997 and 2012, are essentially records of my development as a poet; my encounters with “cultures” beyond the working class I was born into; my interrogations of my own as well as Europe’s histories; my attempts to make sense of the world I live in and the languages of grief, trauma, exile; my efforts to live an authentic life, one which I was always told a bastard dog like me doesn’t deserve.

To stick with the subject of cultural cross-references, I have to ask about your own story. You have parents from very different countries, Sicily and Germany, and you’ve taught in the US and in England, and you spend a good deal of time in Switzerland. No doubt this jumble helps shape the whole book, but I’d like to hear what you have to say about it.

Yes, that’s a question that comes up often during interviews. And it’s a long story, as you can imagine––but here’s the short of it. As an immigrant child born in Switzerland (with a Sicilian father and a German mother), I was always seen as some kind of strange animal with unrealistic dreams, especially when it came to my idea of wanting to be a poet. Swiss society and its educational system did its best to silence my bark and keep my cage locked tightly. I wasn’t allowed to sit my high school entrance exams because I was considered a foreigner. My secondary school teacher told me that “Italian idiots like you have no business going to high school.” I applied for several apprenticeships, but again I was rejected on all fronts. I quickly realized that I had to fight hard to get a shot at higher education and create my own opportunities outside of Switzerland. I eventually got out by tricking a well-known tennis scout in Zurich into getting me a scholarship to attend one of the most prestigious tennis academies and preparatory schools in the US, even though I’d never had a tennis lesson. Nevertheless, I did get my high school diploma, which allowed me to attend an American university, and, perhaps more important, offered me the opportunity to become a writer, a poet, someone who plays with language(s). My self-imposed exile and linguistic suicide, i.e., my decision to write exclusively in English, were necessary for me to live the writing life, to write my own artistic identity and follow the likes of Simic, Brodsky, or Nabokov into the English language, into that translingual non-space I’ve been living in since the age of seventeen. Writing poems has allowed me to live the writing life, to travel the world, to teach thousands of wonderful students in the United States and England, and so much more. My career also serves as a final “fuck you” to my former teachers in Switzerland, but, more importantly, it also proves to so many of my students, for example, that, despite the word on the street, anything’s possible, no matter who you are or where you come from.

Fascinating. Heartening, too, the way you overcame prejudice. If I were to apply the story to a particular poem, that might be “Study in Soot & Hypertonic Saline.” The opening lines combine both “nowhere to go” with the happy notion that “there’s always a carnival.” Does that poem address your own personal mash-up, as I imagine? Or would you single out some other, better example?

I can say that I wrote “Study in Soot & Hypertonic Saline” during my daily train commute from Liverpool to Ormskirk (back in 2009, I think), when I was teaching at Edge Hill University. It addresses notions of exile and trauma, but also the possibility of hope and the need to get to the end of the line by whatever means possible, if that makes sense. I think all of my poems deal with my “personal mash-up,” in way or another. I see my work as one long “confession,” which doesn’t necessarily mean it’s “confessional.” My poems are really about language, the “writing through” of our own myths (we all create our own myths, don’t we?), and how language always finds a way to make us feel restless.

Ah, confession and myth—that takes me to one of the most intriguing poems here, “Trakl’s Season.” Georg Trakl was an Austrian poet from the turn of the previous century, and here in the States I needed research to buttress my crumbling memory, but any reader can see how your poem invests the natural world, like a maple or a breeze, with the power of voice and even confession. So too, it brings ghosts to life, dead soldiers and “ancient pilgrims.” All in all, it calls to mind a far more famous poet, Ovid, and his “Metamorphoses.” What can you say about this remarkable poem and its roots?

Trakl’s ghost haunts all of my poems. I’ve been reading him since I was a teenager, and his unparalleled ability to use a very limited palette of colors and “objects” to create nightmarish visions that hide in plain sight has been a major influence on me. I’ve also been translating and publishing his poems for many years now––see my most recent conceptual approach in ORAKL (Black Lawrence Press, 2017). And somehow he kept popping up during my academic career, especially in graduate school, when I was a working with Franz Wright, Nicholas Samaras, James Reidel, and Daniel Simko, who were also students of Trakl, and who reminded and encouraged me to trust in nature’s voice and record its confessions when I was working on the manuscript of my first collection. Anyway, “Trakl’s Season” is simply an homage to Trakl, an acknowledgment of his influences on my work as both a poet and literary translator. It’s nice to see, however, that the poem is capable of bringing other ghosts to life.

Deeper into DOGS, in the poem “Escape Artist,” you have a line that resonates powerfully, haunting the whole, I’d say. The piece is something of an elegy for your mother, and at one point it offers: “Language, nestled up against silence.” This takes us once more to the concept of confession, speaking up to expose the soul, and again to the notion of the voiceless world having a soul. What can you say about this line, this poem, and their place in the whole?

This one’s tricky for me. The poem is about my mother’s funeral. She killed herself. It is a confession, a record of what happened during the church service. Her coffin went missing, and it took hours to find her. I was still quite young. The rest is in the poem, which also asks: What language can possibly deal with this kind of loss? How do we speak to expose the soul when the soul has been silenced? How do we capture in a poem a world that suddenly lost its voice, its ability to speak to us? I don’t know. But perhaps that’s exactly what I am trying to accomplish in my poems: to find the silences that speak, the silences, as Roberto Bolaño once said somewhere, that are “made just for us.”

Bolaño of course is a powerful artist, but the power of your poems takes different form, more personal, considering the minutiae of experience. I see that in this latest answer, the way the poem reprises the tragic events which inspired it. This takes me to a natural follow-up—if one that’s hard to answer. Still, what can you say about the relation between imagination and the actual, for you? Where does your Muse stand, regarding “what really happened?” If it would help to answer with reference to a specific piece, I suggest “Mountain Life,” which speaks of the writing itself.

The actual and the imagination are one and the same for me, or at least they go hand in hand. At its most basic, writing is the act of translating “the actual,” i.e., phenomena, into a language that attempts to decipher what we believe to be the actual (our trying to make sense of the world), whether we’re talking about emotions, objects, trees, whatever. And it is exactly imagination that allows this process to happen. At best, the result offers us some kind of interpretation of the true nature of the actual, i.e., the noumena, the thing-in-itself. You know, what does it mean to experience true loss? Or true love? Or true depravity? We don’t know. We don’t really know anything about anything. Yet poetry is the only vehicle that offers us the chance to come that one step closer to the thing-in-itself, and imagination (the Muse?) is the secret sauce in all of this; it enables us to at least imagine what the true, unfiltered “actual” of any experience might ultimately feel like. As such, poetry offers possible truths in the absence of any absolute truths. As I always say, in the best of all possible worlds, poetry is supremely important and utterly superfluous; poetry changes everything and nothing at all. What does any of this mean in regard to the poem about my mother? Everything in the poem is true, including the quotations. It happened exactly the way I describe it. I’ll never know what truly happened, though. Have we had enough of my Kantian poetics yet? I think so. Let’s continue to live in uncertainty and imagine what’s possible, then––in and through writing, at least––which is what I did in “Mountain Life,” a poem I wrote almost two decades ago, a poem that has only recently and unexpectantly, shall we say, come to life, with the crucial difference that while the perfect poem still hasn’t and will never arrive, I’m not the one who left on the ferry.

Hm, the poem “came to life,” you say—it became its best self, its “noumena.” Other artists have described this experience, and not just poets. Picasso has paintings that are actually re-paintings; they seemed complete, but he let them lie dormant a while, and then he somehow saw through what was on the canvas to another image, more true. Among your poems, doesn’t one describe just such a process of becoming, namely, “Simic’s Army of Spiders?”

Well, no, “Mountain Life,” a poem that’s eighteen years old, literally came to life, the worst life; my wife and I separated a few years ago, and I’ve now actually lived through its specific details. Like I said, poetry, compared to prose or painting or photography or film, for example, does come closest to truth without ever truly capturing lived experience or the true nature of existence––poetry is forever unfinished; we are forever unfinished. Picasso would agree, I think. He always argued against completion. He destroyed anything that felt complete, hence his search for what’s beyond the phenomena of his work. Now, “Simic’s Army of Spiders” is an ars poetica framed by an imaginary party Simic threw in the basement of his house upon winning the Pulitzer in 1990. That’s it. And that “country of light” you see in the poem, that’s existence’s elusive noumena, yes, and the poet’s corpse, of course. It’s that light that’s in and beyond us all.

Busy spiders, other critters, roots and fruits and vegetables—the natural world keeps burrowing and blossoming throughout. Our conversation makes me think this is part of striving for “noumena;” what is more a “thing itself,” after all, than a flower or beast? In any case, the force of nature lends the poetry a certain optimism, seeking the sun. I see that especially in “Chaos Theory,” with its “harvests amid decay.” How does this reading sit with you?

Yeah, I can see that. There’s a certain optimism there, though the poem speaks of trauma and the impossibility of returning to an old self, the permanence of scars. Here, the (artificial) sun of optimism we all seek is unfortunately hidden away in the root cellar with the rest of the year’s harvest, while we all wander around our fallow gardens, digging in the dirt, searching for one last sign of hope.

Now, perhaps it’s time to lighten the conversation up. Your poems also display an instinct for absurdity, even a sense of humor. At your mother’s funeral, for instance, we hear the babbling of a madman. Juxtaposition like that prompts startled laughter and seems in particular central to “Dominoes–Opening.” What can you say about the strange bedfellows you put together there—and throughout, really?

Absurdity? Sure, I can see that. But “a sense of humor”? You are the first writer or reader who’s ever detected a sense of humor in my work. But I’ll take it. It gives me something to think about. My initial response, however, would still be the same: “I don’t write funny poems”––which reminds me of a Jack Gilbert poem, where he writes, “The Greek fishermen do not / play on the beach and I don’t / write funny poems.” Now madness and the mad is something I’m very interested in, yes, but let’s leave that for another day or question. Anyway, “Dominoes–Opening” is merely an investigation or interrogation of human relationships in a space, or non-space, created by chance and chaos, the make-up of all of our lives, essentially. I’m conscious of the fact I keep trying to avoid answering your questions regarding specific poems––my apologies. I’m unable to explain my poems. If anything, my poems are the explanations, the most direct and concise way for me to talk about a specific subject. And once I’ve done that, there’s no language left. This poem, nevertheless, is important to me insofar as it’s an example of a poetics that is more experimental and linguistically innovative. I believe language is at its best and most charged with possibilities when it’s treated like silly putty, when juxtapositions, for example, develop naturally, when the poem on the page “performs” rather than “produces” language––the poetry of saying versus the poetry of the said, as Robert Sheppard puts it. I would say there’s a nice balance between saying and said in DOGS––something for everyone, I hope.